I spent last Sunday and Monday in New York, at the HUC-JIR campus, attending the Jewish Organizing Institute and Network for Justice (JOIN for Justice) first National Summit, the organization’s first. I heard about it through Jews United for Justice, one of my favorite D.C. organizations. As a rabbi, I want to do organizing, so it was a good opportunity to network with other Jews doing social justice work. Indeed, those two days I walked around thinking, “Yes. These are my people.”

Simply put, the conference was awesome, for little and big reasons. I am dork, so I really liked that everything ran on time and stuck to the schedule. (Not everyone showed up on time to sessions (myself included on one occasion!) but that’s a different kettle of fish.) Every session I attended had a written agenda of what was to be covered, and in good organizing fashion, the agenda was reviewed and affirmed before each session. What can I say? I like knowing that presenters know what they’re doing.

The conference also got me super excited about moving to Boston. Bostonophiles had told me what a great city it is for social justice, but seeing is believing. I heard about so much good work going on and/or based there (where JOIN itself is located!), through Moishe Kavod House, Jewish Association for Law & Social Action, Massachusetts Senior Action Council, Boston Workman’s Circle, Keshet, Jewish Community Relations Council of Greater Boston, and more. I’m thrilled about the potential opportunities I’m going to have in rabbinical school.

And I heard some downright inspiring speakers: In the opening assembly, Simon Greer of Nathan Cummings talked about the Jewish legacy and future of social justice: “At the March on Washington, Jews blended in; at Occupy Wall Street, Jews stood out.” Ai-jen Poo of the National Domestic Workers Alliance spoke about community/labor coalition building: “All progressive movements, worker-related or not, bank on the utilization of the labor movement. We have to lift it up.” Marshall Ganz of the Kennedy School highlighted the necessity of a moral aspect to social justice work: “One cannot long last as a light to the world and a darkness at home” (in reference to the occupation of Palestinian lands). Gordon Whitman of PICO emphasized the importance of religious Judaism: “We can’t have just a secular Jewish social justice movement.” Nancy Kaufman of the National Council of Jewish Women: “Social justice comes from Jewish values — but has universal goals.”

One of my favorite sessions was “Mindfulness and Organizing Work,” led by Rabbis David Adelson and Lisa Goldstein. I really identified with Rabbi Goldstein’s section on text study as a mindfulness practice. As she noted, looking at a piece of text is the default Jewish spiritual practice in organizing — but doing so often puts participants into an intellectual space that can be anxiety-producing and can lead to tearing others down. “How can I demonstrate that I know more about Judaism than others? What if I don’t understand what someone else says? How can I show my independence of thought by disagreeing with the author?” Instead, Rabbi Goldstein suggested looking at text from mindful perspective: “What it wise, beautiful, true, or helpful about this text? What does this text teach me about myself and about where I am in the world?”

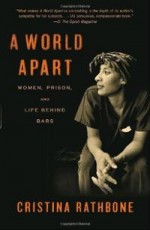

the prophet isaiah (i love the prophet art at huc!); photo by salem pearce (via instagram)

Personally (as opposed to professionally), my favorite part of the conference was seeing my old friend David Segal (now Rabbi David Segal). We hadn’t seen each other since high school, when I was his yearbook editor. We’d friended each other on Facebook within the past couple of years, so we had some idea of what the other was doing. But because of the time built into the schedule for relational meetings (thanks, JOIN!), we were able to make that deeper connection as adults and as organizers. I got to hear about his path to the rabbinate and to Aspen, and I got to tell him about my path to Judaism and to the rabbinate. When we parted, headed to different sessions, he told me a story that gave me chills.

A friend of his, also a convert and a rabbi, shared with him a midrash (or perhaps a midrash on a midrash?): Between creation and when the Israelites went out of Egypt, G-d is said to have visited and offered Torah to all of the nations of the earth, who ultimately rejected it; only the Israelite nation, at Mount Sinai, accepted it — becoming the “chosen” people. David’s friend noted that in each of the rejecting nations, though, a few people in the back of the crowd raised their hands and said, “Wait! I want it.” That is him, he said.

That is me, too.